To Kill a Mockingbird

adapted by Christopher Sergel

based on the novel by Harper Lee

Pickwick Players

February 17 - 26, 2017

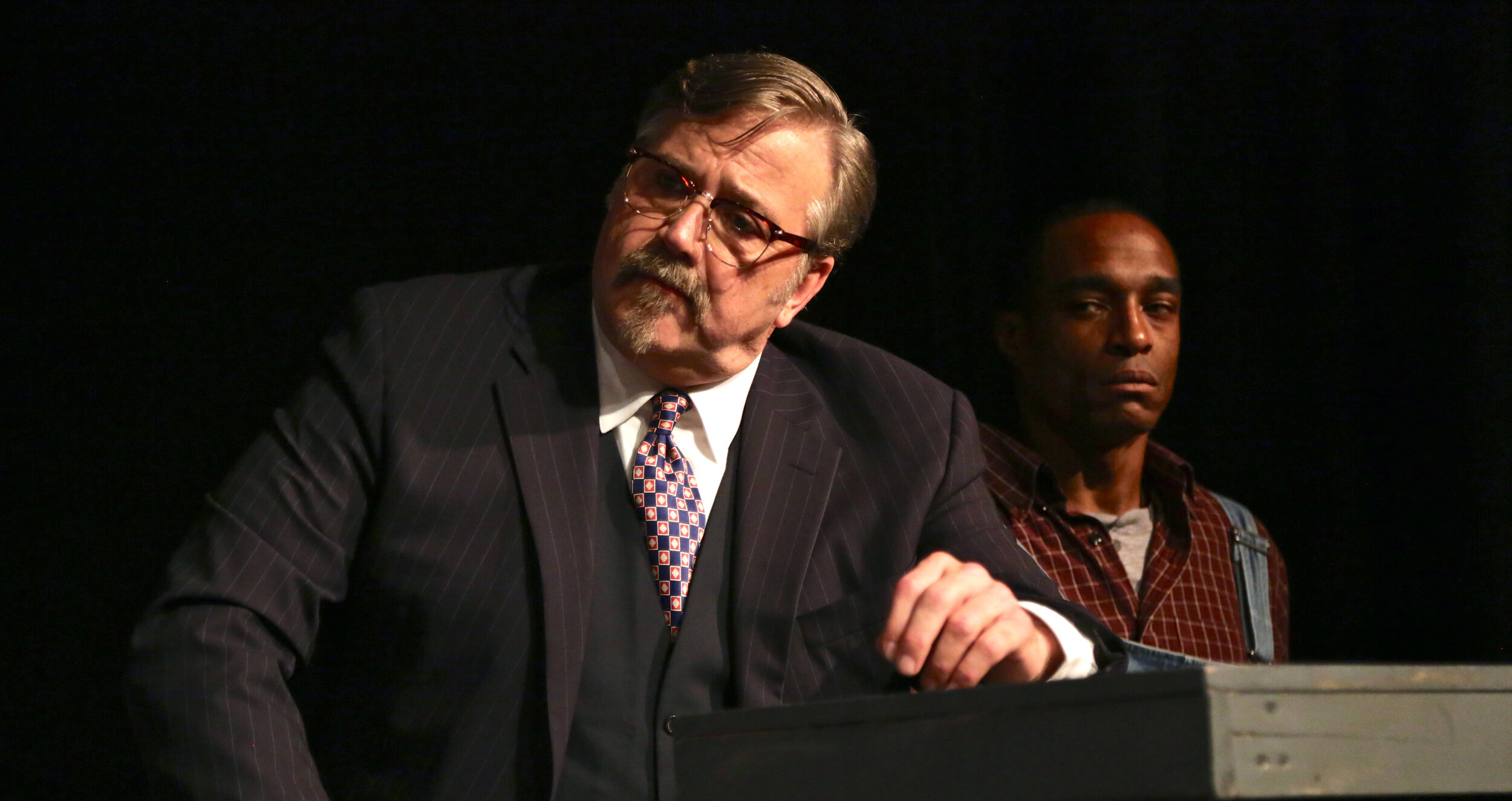

When I was initially asked to direct To Kill a Mockingbird in July of 2016, I could not have imagined how cathartic the process of creating and presenting the story would be when it finally hit the stage in February of 2017. The election of 2016 loomed over the production process - forging an incredible bond within the cast and prompting conversations about race, equality, and justice that impacted actors and audience alike. The production forced us all to look at our neighbors with new eyes - always hoping that Atticus Finch was right and that you can’t really know a man until you’ve walked a mile in his shoes.

The production marked my first foray in directing in nine-years (my last production having been mounted in 2008) and I was excited but trepidatious about the opportunity. I committed myself to bringinging the story to life in the best ways I knew how: research and visual art.

I dove into textual evaluation and excavation - tearing through multiple versions of the script, the novel, biographies of Harper Lee, interviews, and research about Alabama in the 1930, including details about sharecropping, lynchings, the economics of the Depression (and, specifically how that impacted the South), and American folk music.

I devoured the photography of Dorthea Lang and Walker Evans, as well as other photographers and painters of the era (the works of Grant Wood made a particularly strong impact on the visual palate of the production). Amassing specific details for the actors and designers gave me a sense of the play as a living experience before we even entered auditions. Doing the “homework” ensured that my return to directing would yield a result about which I would be proud.

Design and approach.

Dorthea Lang.

The photography of Dorthea Lang and her study of California sharecroppers in the mid-1930s (through the Resettlement Administration / Farm Security Administration) was used as inspiration for both the physical design of the production (costuming, sepia-toned lighting), but also the emotional context of characters. Her famous photograph, Migrant Mother, directly influenced the physical life of the actor playing Calpurnia - right down to the way she put her hand to her mouth.

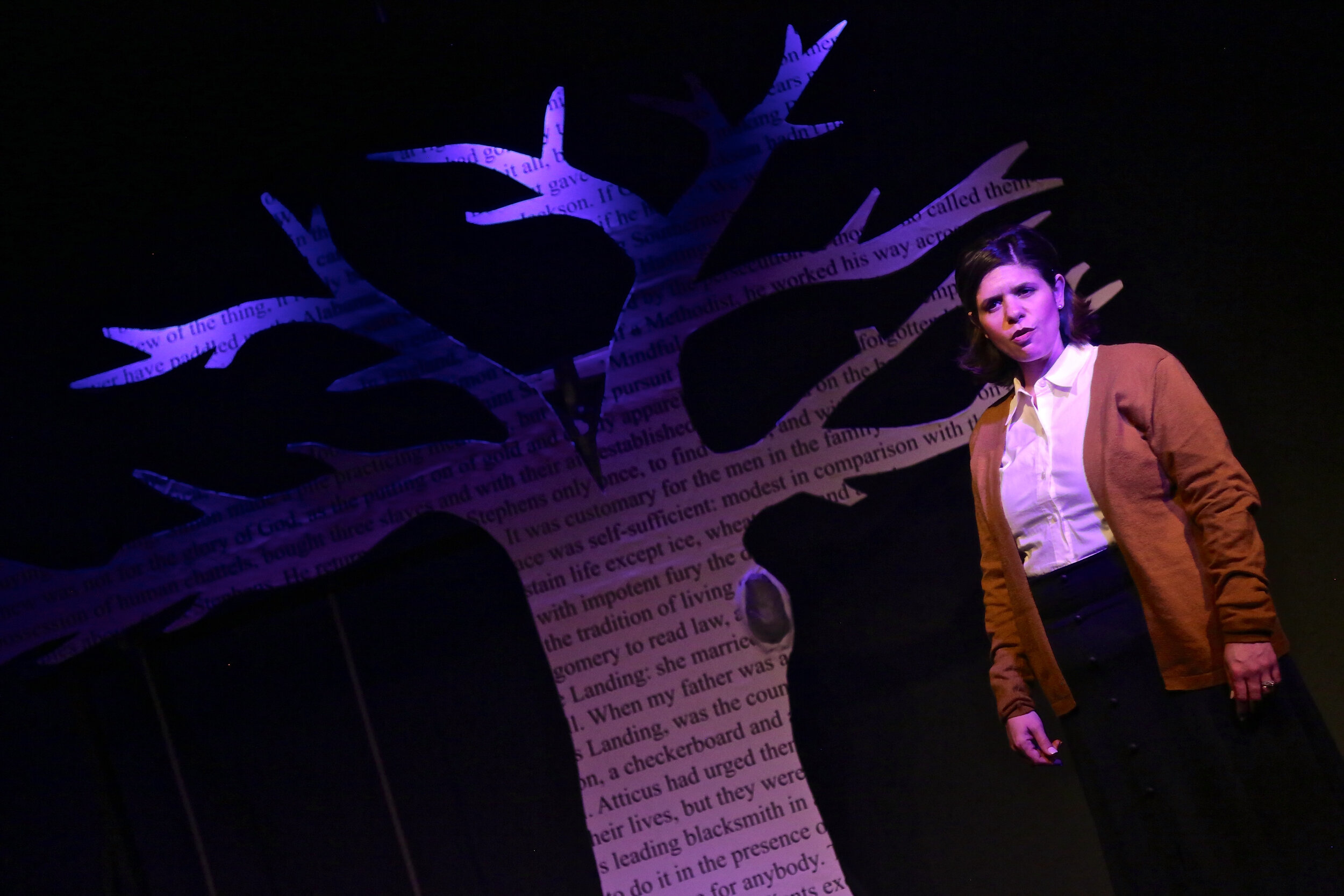

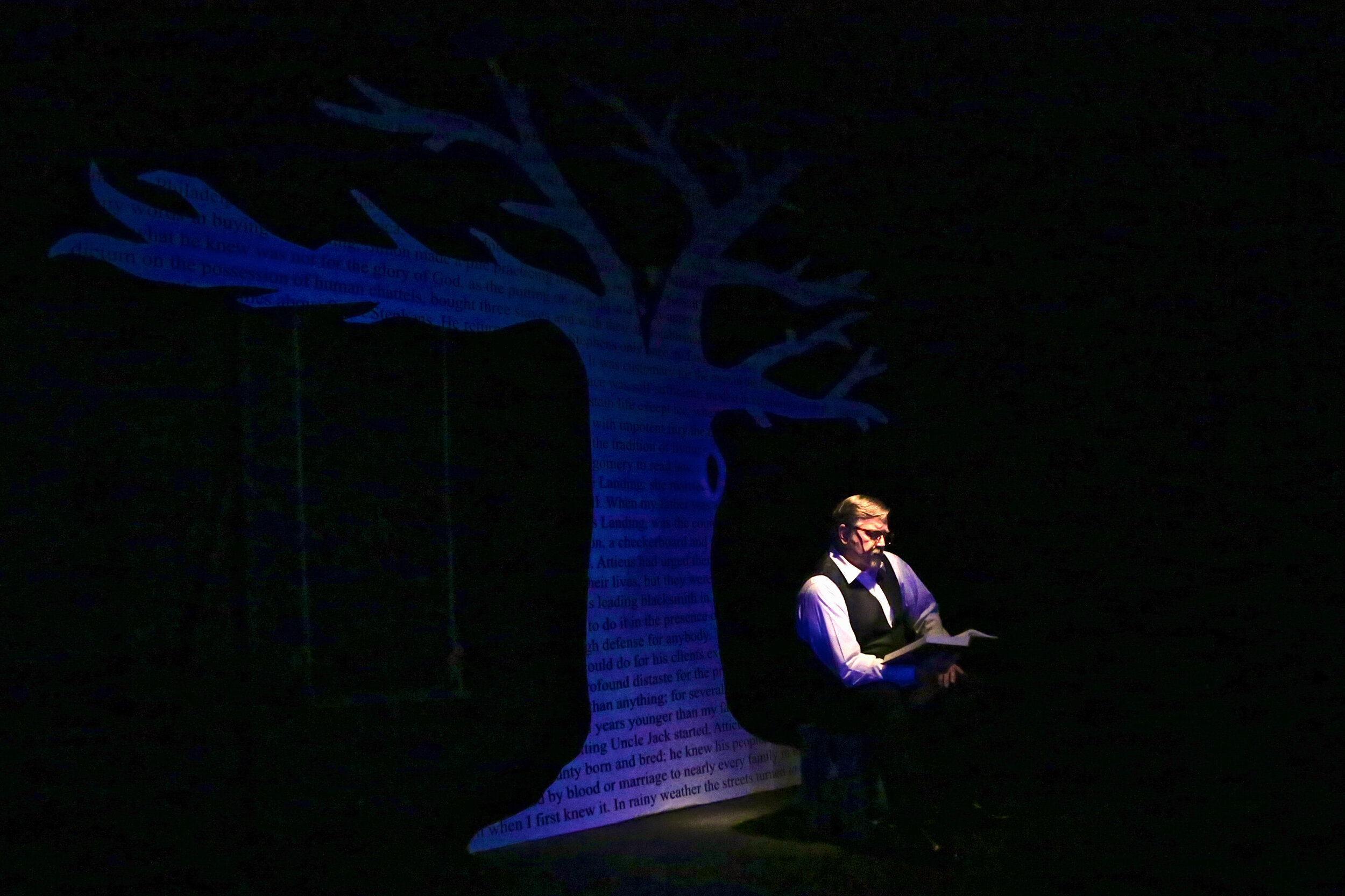

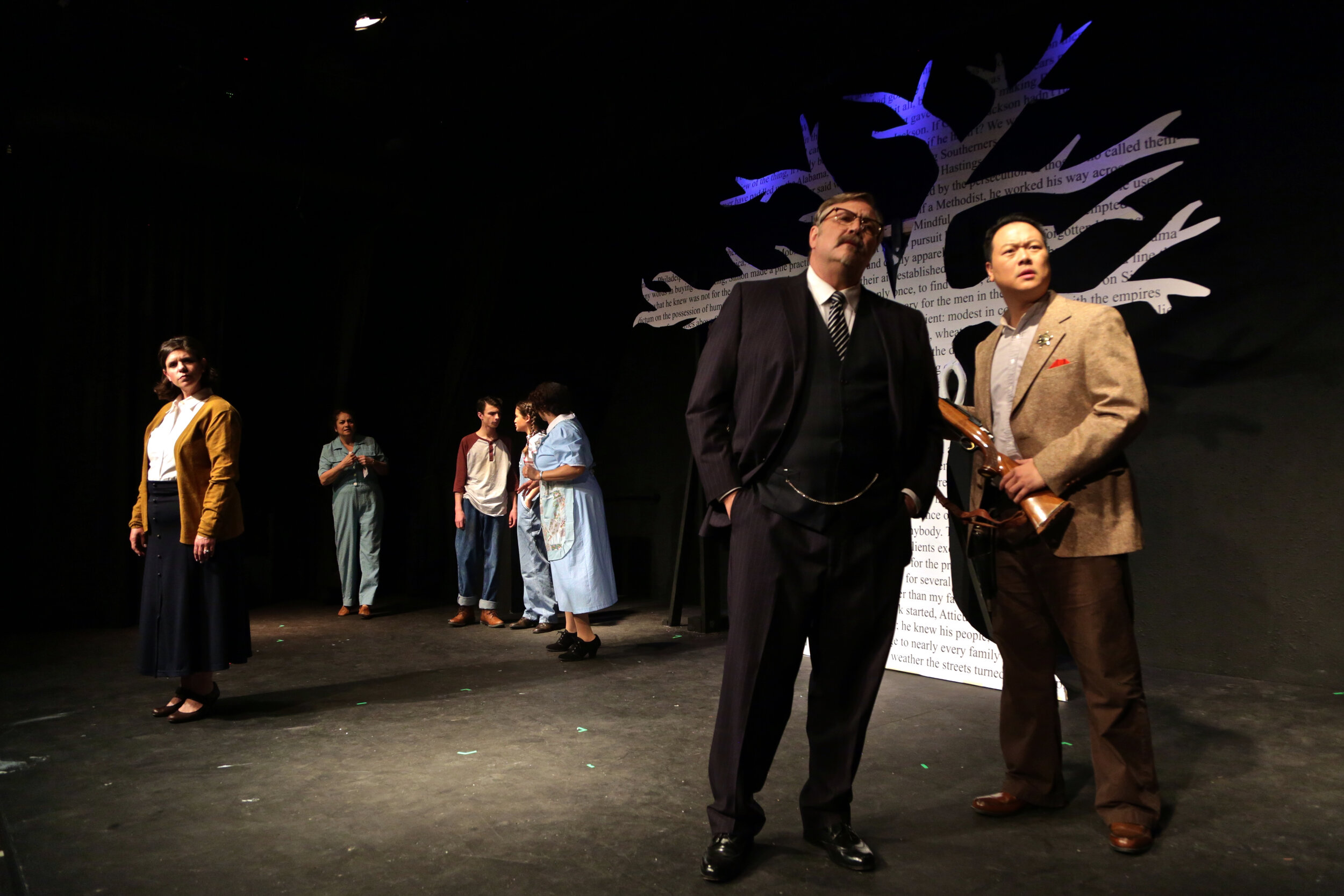

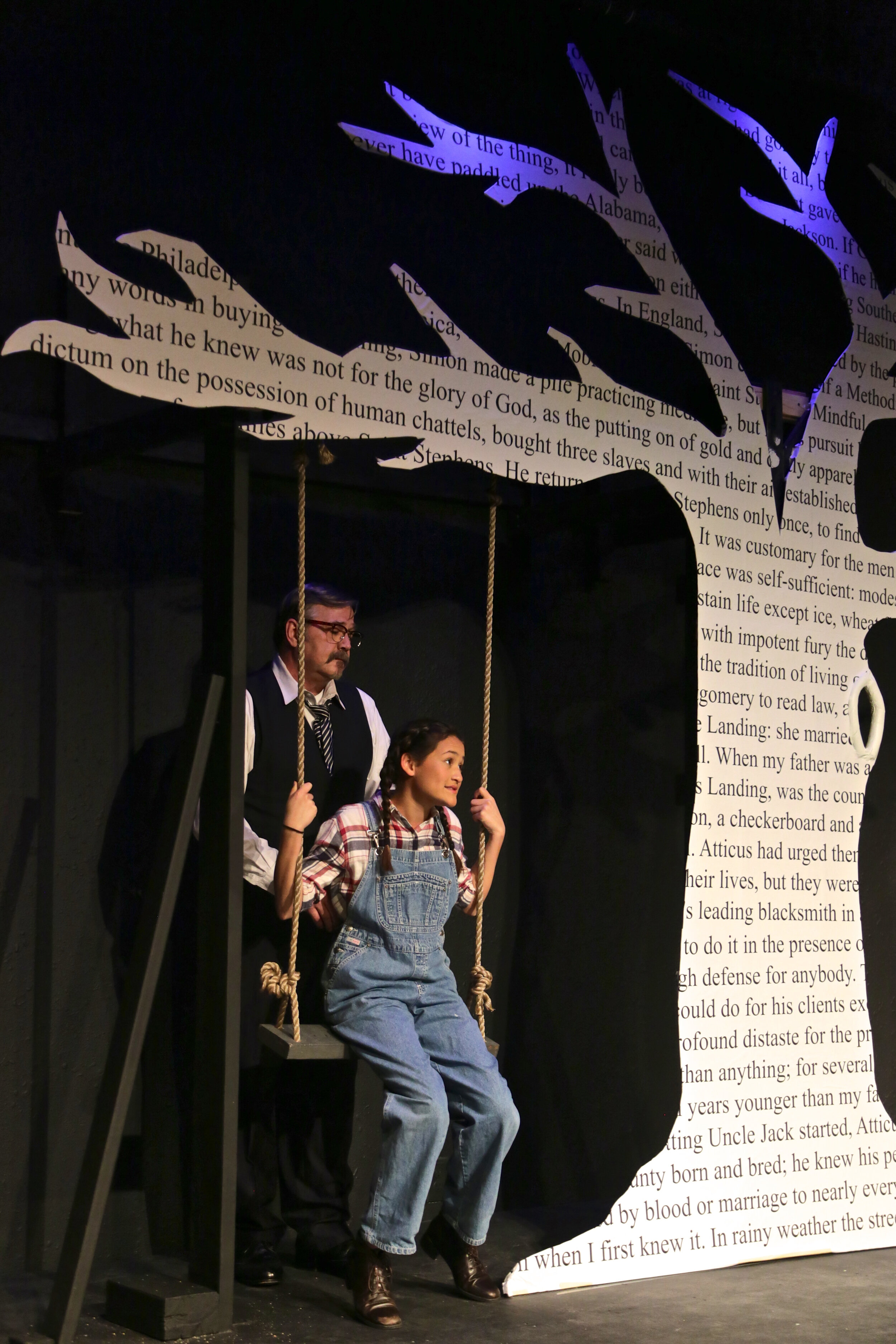

Boo Radley tree.

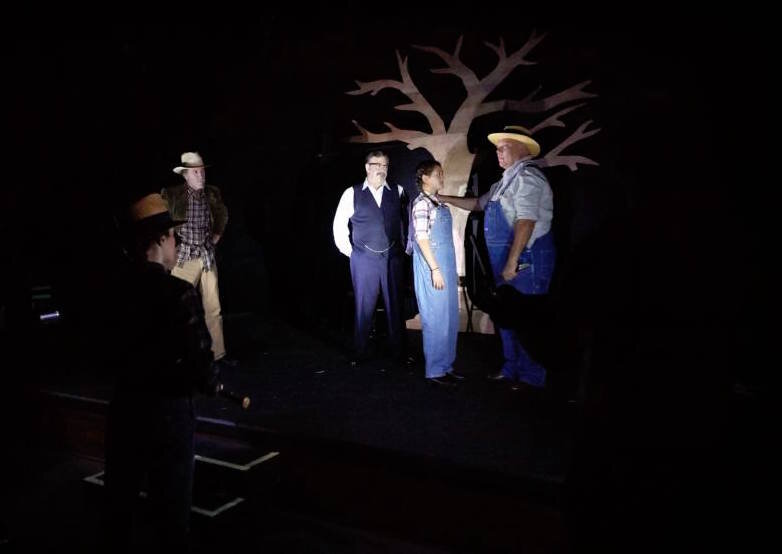

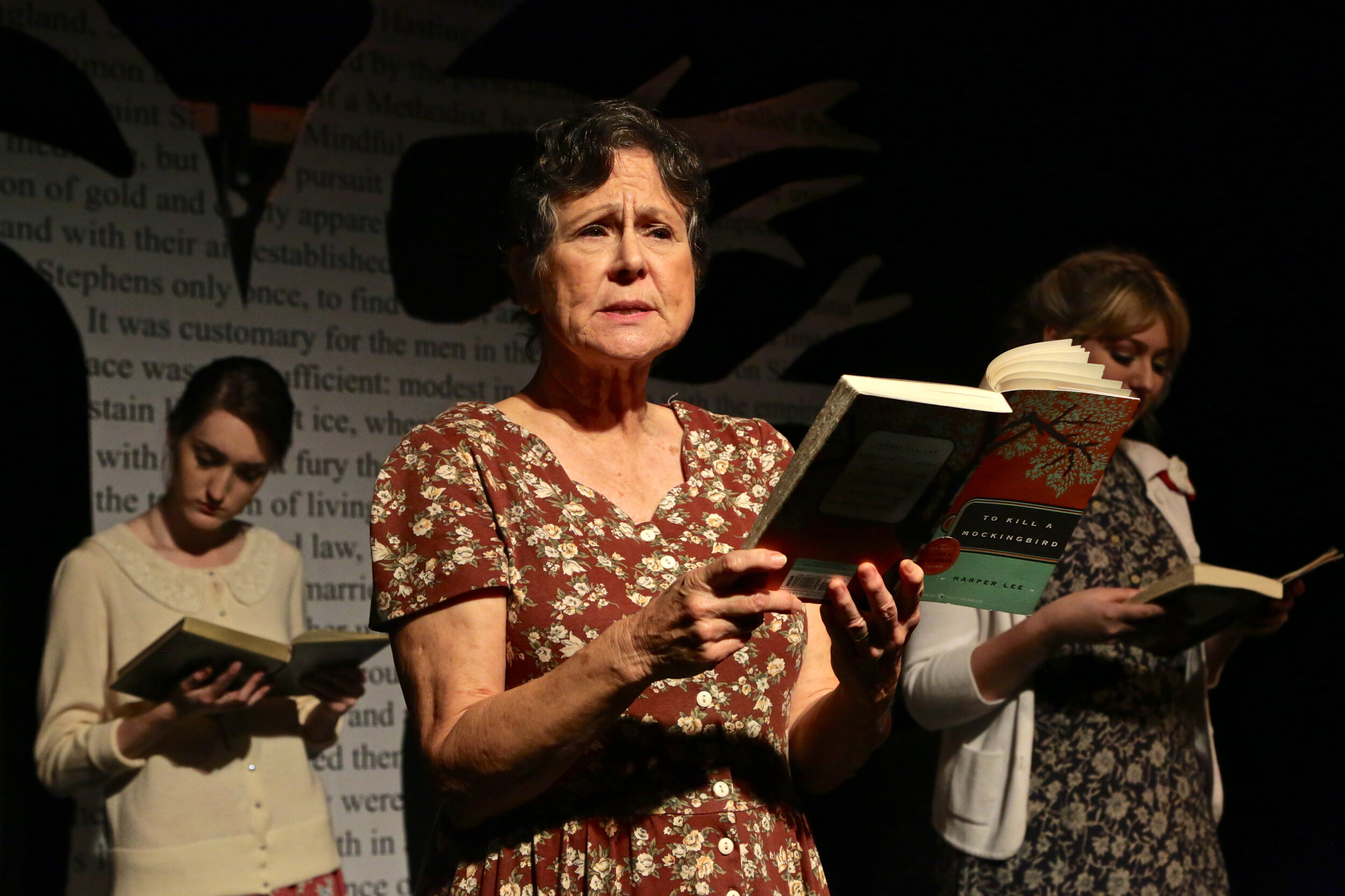

I was committed to bringing an element of the text onto the stage - to reference the fact that the play was based on Harper Lee’s amazing novel. The set was designed around the image of the Boo Radley tree (with a working swing set added for the kids to play with) covered in the opening pages of the novel. I wanted to physicalize the importance of the novel’s words by placing them in the center of the stage. The overall design for the production was very sparse - with fruit crates used for seating, doors on a-frames used for tables, with no structures (other than the tree) to adorn the stage. We trusted the imagination of our audience (much like Harper Lee trusted the imagination of her reader) to fill in the gaps and create the world of Maycomb around us.

Walker Evans.

Now Let Us Praise Famous Men, Walker Evans study of tenant farmers in the American South (with text by James Agee), gave context to the lives of the residents of Maycomb, Alabama in the mid-1930s. Evans’ images provided the cast and creative team with an understanding of characters they were bringing to life - their social status, their labors, how they related to their fellow residents. Evans’ work, along with the photography of Dorthea Lang and specific works by Norman Rockwell informed the creative team’s approach to lighting, costuming, and setting.

Story on PBS.

The production was lucky enough to receive notice from KPBS (San Diego’s local PBS and NPR station). The story about the production, ran locally in February, 2017.

Photo Credits

Photos courtesy of Adriana Zuniga Williams, with select images by Darin Fong.